Dr. Valentina DeNardis is the Director of Classical Studies at Villanova University and a Microsoft Innovative Educator Expert. She’s embarked on some ambitious digital projects to help bring antiquity to life. Most recently, her students used Minecraft: Education Edition to construct digital recreations of ancient monuments and scenes from Classical literature. She shared her story in this guest post!

A few years ago, inspired by the virtual heritage work of Microsoft A.I. and Iconem, two of my Classics students and I worked on creating a virtual reality experience of the ancient Athenian acropolis. The digital model of the acropolis and accompanying interactions we built into the project were developed for educators and students to explore in Villanova University’s Immersive Studies CAVE, an 18×10-foot virtual reality room.

V.R. Acropolis at the Villanova University Immersive Studies CAVE

V.R. Acropolis at the Villanova University Immersive Studies CAVE

Zackary Hegarty, an M.A. in Classical Studies and current Ph.D. student in Informatics and Virtual Heritage at the University of Indiana, did the coding for the project, and Claire Hoffman, who holds a Bachelor of Arts in Classical Studies, created image and text panels which would pop up when interacting with the digital acropolis. This project was a huge undertaking, especially for students who had little to no background in coding. The blending of our humanities studies with computer science skills was something I wished to continue and encourage my students to explore. I wondered how to get younger students interested in the emerging field of virtual heritage in a practical way.

In fall 2019, I was teaching an undergraduate course in Roman archaeology, and I had planned to have students make a few sketches of the ancient Roman monuments we were studying. Then it occurred to me that I could have them build digital models of these monuments in Minecraft! I had never tried Minecraft myself—though my own children loved it—and I was pleased to discover that Minecraft: Education Edition has a wealth of helpful resources to get educators started.

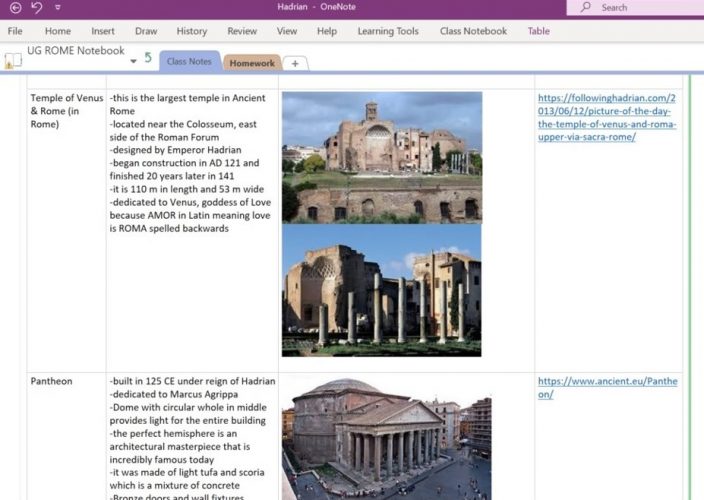

For my course site, I created a class team in Microsoft Teams. Each week I would typically have students research different Roman monuments related to the time period we were studying. Students recorded their research in their individual notebooks within our class team’s OneNote Class Notebook, posting notes, photos, videos, and links in a table on the assignment page. The flexibility of the type of content you can add to a OneNote page is particularly useful for a course like this.

Student research in the OneNote Class Notebook

Student research in the OneNote Class Notebook

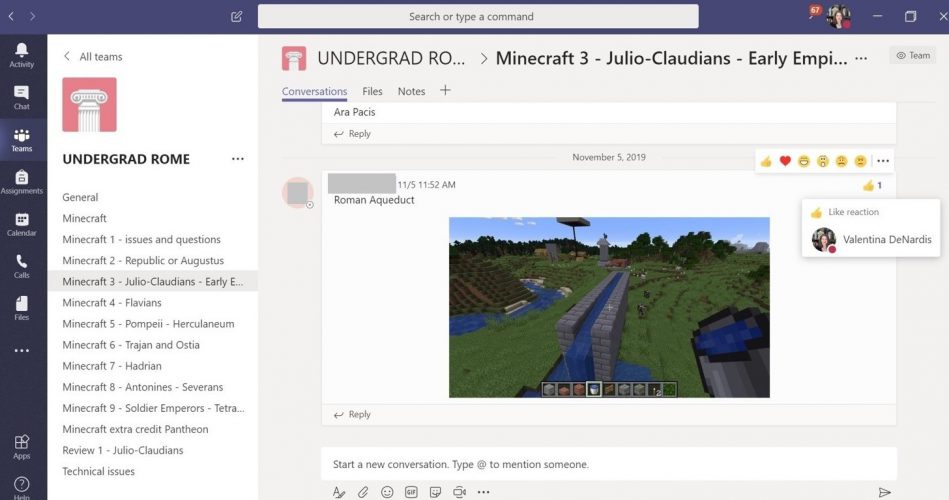

When the students had completed their research on various monuments related to the week’s topic, they chose one to recreate in Minecraft. Some students had more experience with Minecraft than others, and I was heartened to see them help each other as they developed their skills. Once the students were satisfied with what they had built, they took a screenshot and posted it in the chat space of the appropriate week’s channel in our class team. Students could then see each other’s reconstructions, as well as like and comment on them. The chat feature in Microsoft Teams was a wonderful space for students to share their work and collaborate.

Student work shared in the Microsoft Teams chat

Student work shared in the Microsoft Teams chat

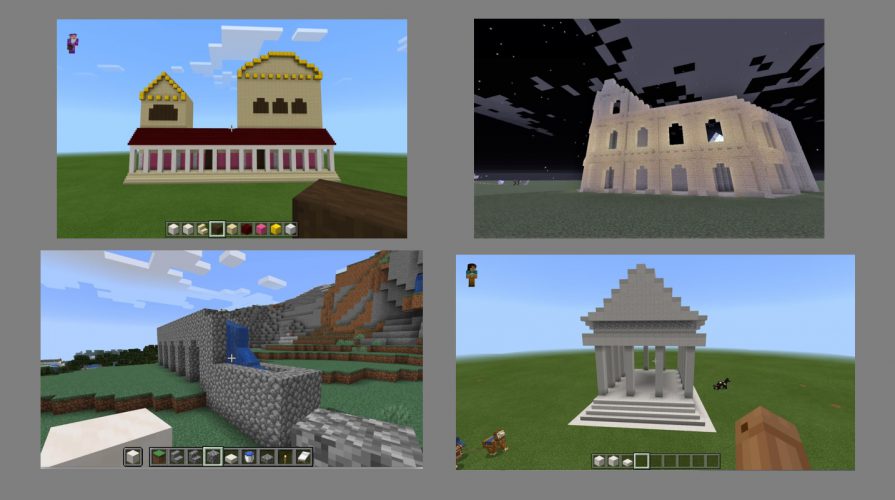

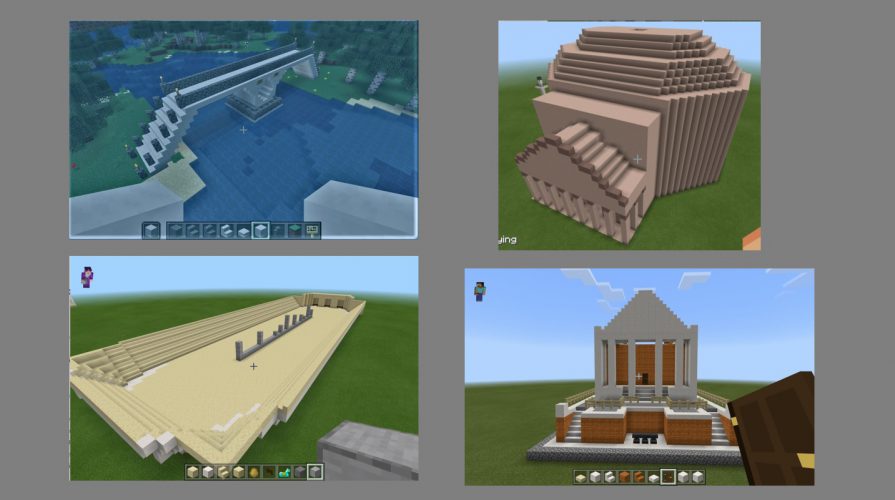

Through rebuilding the Roman monuments in Minecraft, the students developed a deeper understanding of how these monuments were constructed. They also got a taste of the field of virtual heritage, which preserves ancient monuments in digital form for future generations to study. Students had the choice of recreating the original form of a monument or representing what remains of that building today. Here are some examples of my students’ work:

(Clockwise from top left) Roman Curia, Colosseum, Temple of Portunus, Roman aqueduct

(Clockwise from top left) Roman Curia, Colosseum, Temple of Portunus, Roman aqueduct

The image below includes a reconstruction of a Roman bridge which has been in use since it was built in the first century BCE. The student who created this model included the Latin inscription, still visible today, that records the name of the original builder of the bridge.

(Clockwise from top left) Pons Fabricius, Pantheon, Circus Maximus, Temple of Divus Iulius

(Clockwise from top left) Pons Fabricius, Pantheon, Circus Maximus, Temple of Divus Iulius

After this successful experience with digital reconstruction in my Roman archaeology class last fall, I decided to develop a Minecraft project for my intermediate Latin class in spring 2020. The bulk of our class was focused on translating and analyzing the Latin from book four of the Roman poet Vergil’s Aeneid, an epic poem about the journey of the Trojan hero Aeneas in his quest to found what eventually came to be Rome.

To provide some context for the section we were reading in Latin, I asked students to read an English translation of the other eleven books of the epic. For an end-of-semester course project, students were tasked with choosing five scenes from the Aeneid and recreating them in Minecraft. While scenes from Roman legends and myths were often represented in ancient art, such as mosaics, frescoes, and sculptures, this proved to be an interesting challenge for students since they had to decide which moment of a scene could be rendered well in a digital format.

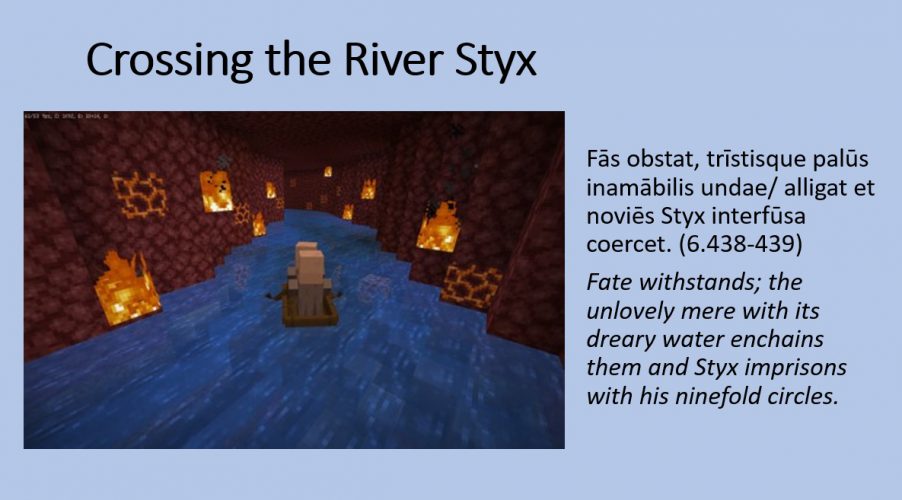

As in the Roman archaeology class, students shared screenshots of their work in the chat space of our class team. For the final project, students were asked to collect all the screenshots of their scenes, along with accompanying Latin text and translation excerpts they obtained from online open educational resources. They could submit their project in the form of a PowerPoint or Microsoft Sway. Here’s a slide from one student’s PowerPoint, depicting the crossing of the River Styx by Aeneas and the Sibyl:

A student’s reconstruction of the River Styx scene from Vergil

A student’s reconstruction of the River Styx scene from Vergil

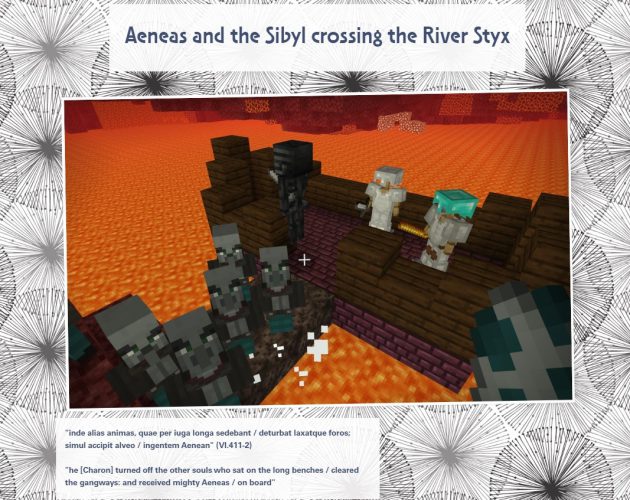

Another student recreated the same scene but focused on Aeneas and the Sibyl meeting Charon, the ferryman, who would transport them across the river. This student chose to present her work in a Sway:

A student’s reconstruction of Charon scene from Vergil with text

A student’s reconstruction of Charon scene from Vergil with text

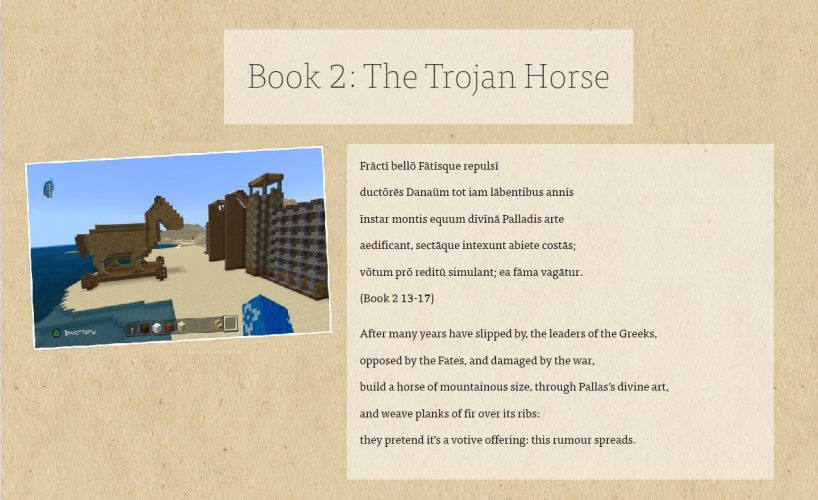

A popular episode in the Trojan War legend is the tale of the Trojan Horse, which the Greeks used to convey hidden soldiers inside the walls of Troy. Here’s one student’s reconstruction of this scene, presented in a Sway, followed by a close-up view of the Minecraft scene:

A student’s reconstruction of the Trojan horse scene from Vergil

A student’s reconstruction of the Trojan horse scene from Vergil

While the main focus of this class was to translate the Latin text of Vergil, students reported finding the Minecraft project immensely helpful in visualizing the scenes from the epic poem. One student remarked that this activity made Latin more fun, and I can attest that their creative digital reconstructions brought the ancient words of the Latin poet to life.

Minecraft has proven to be an excellent tool with which students can investigate the ancient world and begin to learn how to preserve the cultural heritage of bygone civilizations for future scholars to study and explore.

***

It’s inspiring to hear about the original and imaginative ways educators are using Minecraft to bring their subjects to life! You can find lessons and resources for engaging with the ancient world in our History and Culture Subject Kit. If you’re new to Minecraft: Education Edition, learn how to get started at education.minecraft.net.

The post Exploring Virtual Heritage in Higher Education with Microsoft and Minecraft appeared first on Minecraft: Education Edition.

This post was originally published on this site.